Part 3: Making It Personal

Aug 16, 20213. A Way to Understand “Joy” that Avoids the Tangle of Vocabulary.

As we seek to discuss the concept of “joy,” we will not seek a definition, but we will seek a way to operationalize the concept. I have said elsewhere that “operationalize” is an intentionally “ugly” word: its ugliness reminds us that whatever way we have found to talk about a concept such as “joy,” we are only talking about some sort of approximation to the concept, not the concept itself.[1]

Can we operationalize “joy” in terms of “fun?” Joy is not the ability to “have fun,” because even the joyless have “fun.” However, we cannot conceive of “joy” without some “fun” involved. A problem is that “fun” is highly subjective, and what is fun for one person is absolutely not fun for another. To take an extreme example, the scholar of antiquities finds fun in spending hours examining manuscripts and artifacts, something most people would find absolutely boring. As it happens, the scholar rejoices at the prospect of studying an artifact or manuscript, especially one that no other expert has encountered.

In contrast, consider those who participate in dog fights or cock fights. I once served on a grand jury that was required to study evidence related to dog fighting, an absolutely illegal activity. It became clear that there is a large underground dog fighting industry that is quite sophisticated. There are internet web sites that detail the fight records of hundreds of dogs so that an aficionado can place an informed bet. The fights take place in arenas located at the end of dead-end dirt roads, and everyone knows whether someone traveling such a road “belongs” or not. Strangers who travel these roads do so at the peril of their lives.

Going to Heaven – The most popular religion was that of Dionysus, and it was a religion of drunkenness. Heaven was considered to be a state of perpetual drunkenness. This scene from a sarcophagus shows the deceased (a really chubby guy) dead drunk and being carried into heaven by friends. The full sarcophagus shows him being followed by a long parade of gods and exotic creatures. From the Glyptothek, Munich, Germany.

Going to Heaven – The most popular religion was that of Dionysus, and it was a religion of drunkenness. Heaven was considered to be a state of perpetual drunkenness. This scene from a sarcophagus shows the deceased (a really chubby guy) dead drunk and being carried into heaven by friends. The full sarcophagus shows him being followed by a long parade of gods and exotic creatures. From the Glyptothek, Munich, Germany.

For those involved, dog fighting is “fun,” and they no doubt have a stock of jokes they share with one another. However the lives of breeders and owners seem to be utterly joyless. They certainly do not love their dogs, and it appears that they do not find joy in their relationship with their dogs. They live a life of desperation, often one fight away from economic disaster. It is a life of fear from the law and fear from those above them in the “pecking order.” Perhaps we have said enough to make the point about “fun.”

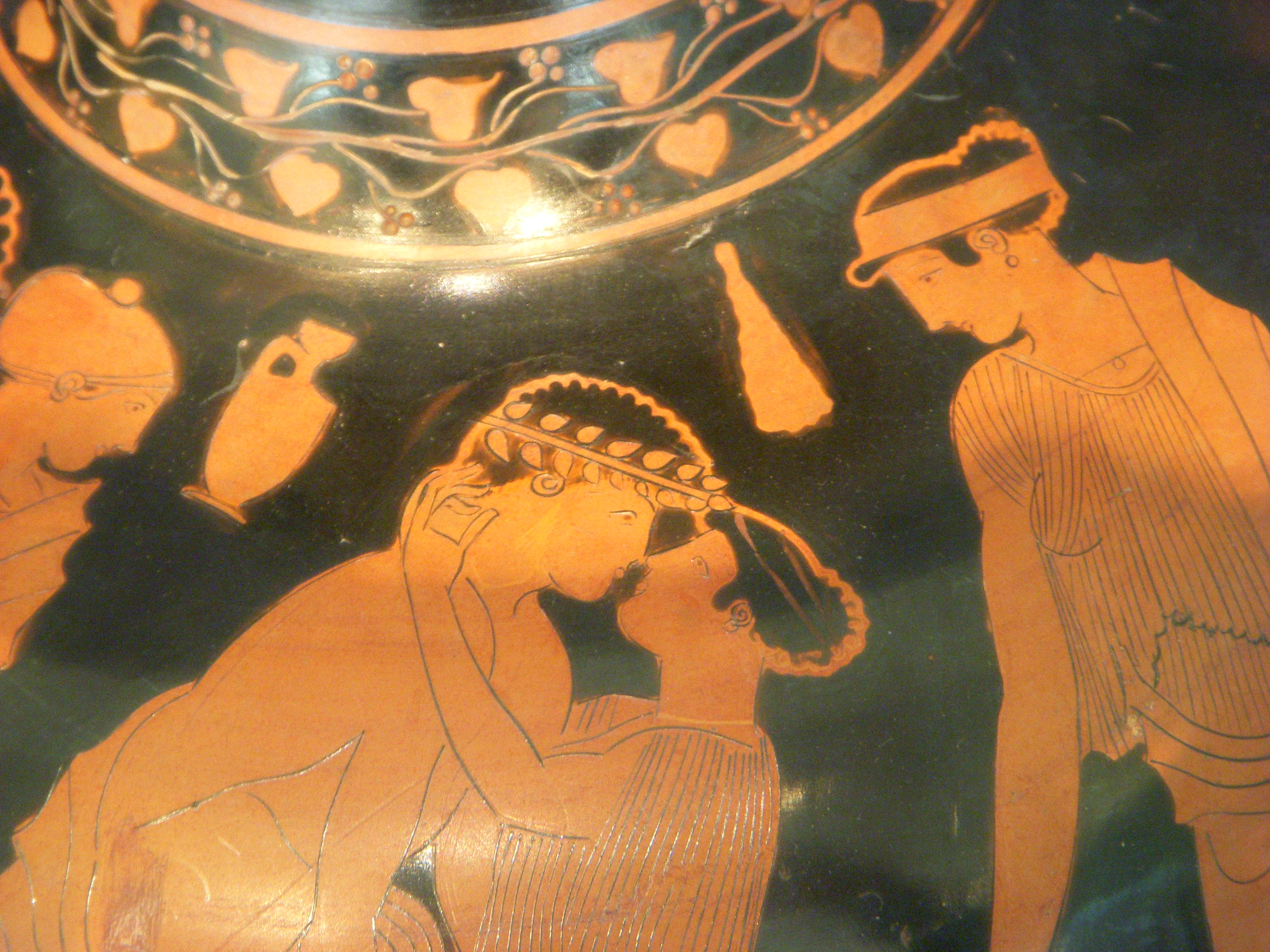

Surprise kiss – Romance is found in every society and culture.

From the Art Institute of Chicago

What about “happiness?” Maybe “happiness” is better than “fun” as a way to talk about (operationalize) joy. Once again the concept is highly subjective, but it seems that happiness is closer to joy than is fun. As it happens, there is a “World Happiness Index.”[2] It is based on answers to questions asked in the Gallup World Poll. Respondents are asked to “think of a ladder, with the best possible life for them being a 10, and the worst possible life being a zero. They are then asked to rate their own current lives on that 0 to 10 scale.” Responses are subjected to technical statistical analysis which need not concern us here.

In addition to these responses, the survey looks at six other bits of information for each country: levels of GDP, life expectancy, generosity, social support, freedom, and corruption. The “key findings” are of interest to us:

people like living in communities and societies with less inequality of well-being, and where trust – of other people, and of public institutions – is high. People in high trust communities are much more resilient in the face of a whole range of challenges to their well-being: illness, discrimination, fear of danger, unemployment, and low income. Just to feel that they can count on others around them, and on their public institutions, makes their hardships less painful, thereby delivering benefits to all, and especially those most in need.[3]

This statement does not qualify as a “definition” of a joyful society, but it gives us a good indication about important elements of what we might call a joyful society. Among other things, a joyful society will experience a relative equality of well-being and it will be a society in which people can trust one another and trust the government.

Beyond this, we can intuit some other elements. There should be freedom from fear (one of Roosevelt’s “four freedoms”). This follows from the element of “trust,” but we should be specific about freedom from fear.

Likewise we should be specific about optimism, which seems related to both equality of well-being and to trust. Optimism must be distinguished from the proverbial attitude of Pollyanna or the attitude of Voltaire’s Candide. A desk dictionary offers the “Pollyanna” definition of “optimism”: “A disposition to expect the best possible outcome . . .” (emphasis added), but it seems more suitable to define “optimism” as “a disposition to expect a good possible outcome,” or even “a disposition to expect an outcome that is not bad.”

A theologian can find fault with the elevation of optimism to any understanding of joy because the world is in a mess and Christians share joy in the hope that God will ultimately clean up the mess. Peterson says, “The world’s alternative to salvation is optimism. . . . As long as they can rationalize, fantasize, or interpret the catastrophe as something considerably less than catastrophe, they can deny their need of God for salvation, either for themselves or others or the world.” Before this, he spoke of “catastrophe” this way: “The dimensions of catastrophe are understood, biblically, to exceed human capacity for recovery.”[4]

Our theme picture is a Dionysaian portrait of young woman

– from Glypthothek, Munich, Germany.

This is a masterful representation of emotion.

We have not been discussing Christian joy as dependent on Christian hope, but joy as a characteristic of a culture and society. The joy we are discussing is tied to secular hope for tomorrow, the hope that tomorrow the family will be intact (no one will die tonight, no one will be murdered in the street, etc.) and that tomorrow there will be adequate food. The hope to be sheltered from extremes of weather with adequate shelter and clothing. The hope not to be oppressed into involuntary servitude.

The difference between Christian joy and secular joy is that while Christians hoped for tomorrow in the same way as others, they were prepared with something more substantial than Stoicism to retain their joy even when the hopes for tomorrow were dashed.

Our point about secular joy is that if the populace does not think there is a high probability that life will be good tomorrow, then, in that society, joy will be low. St. Paul’s teaching about Christ may have led to a new understanding of joy, but it didn’t instantaneously transform the hopes of the Roman populace.

[1] Davies, Richard E. Handbook for Doctor of Ministry Projects: An Approach to Structured Observation of Ministry. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1984, pp. 99-100.

[2] https://worldhappiness.report/faq/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Peterson, Eugene H. Reversed Thunder: The Revelation of John and the Praying Imagination. HarperSanFrancisco, 1988, pp. 152, 154.